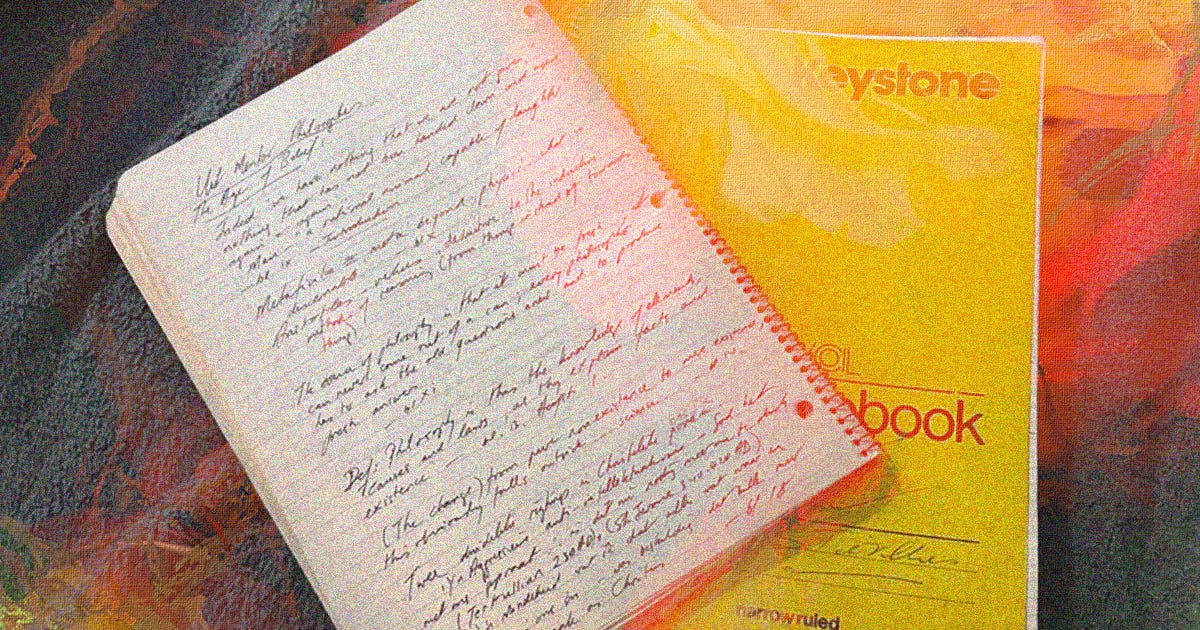

Earlier this month, as I was packing up our storage locker for our upcoming move, I came across a box containing two yellow spiral bound notebooks. I immediately recognized them as a present from my father, that he gave me back in 2004, when I visited him for the last time at his home in Pretoria, South Africa. That visit turned out to be the last time …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tilted Windmills to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.